What is the quest design of Lord of the Rings?

That’s the question that started me down a winding path and led me on my own grand adventure of discovery and personal growth, and that’s the question I’m here today to help answer.

In this article I’m going to look at quest design in a variety of non-games ranging across nearly every genre I could find. By the end of this article, I’m hoping you can walk away with a better understanding of how to look at media in order to learn about game design, specifically focusing on quest design.

Will you accept this mission?

[Yes] / [No]

Ok, so that was cheesy, but I did that to highlight something. In games we’ve arrived at a convention with our quest-givers, in that we expect there to be one. We expect to see an NPC standing around with a big icon over their head telling us that we need to help them by going off into the forest and killing fifteen Dire Rats, or whatever. At least that’s what we expect in open world titles. When you look at a game like Tony Hawk Pro Skater, you get quests simply by choosing the location where you want to play, and you’re given all the various quests for that area when you arrive there. Mario 64 is another game where you are given quests based on selection of an area, but in that game those quests are accessed linearly. JRPGs, like Final Fantasy, tend to string you along on one giant series of quests, dropping sidequests for you as a diversion to keep up the pacing (and doing so in a way very similar to the exclamation-over-the-head style of quest giving).

But what about other media? How does our hero get a quest in a film? Or a book? What are their narrative devices? And once we’ve gotten the quest, what maintains interest as we go about the task of completing it? After that, what do we get as a reward for completing the quest?

I’m looking at a number of films (many of which are based on written stories) to answer those questions. The stories were chosen for a combination of reasons, some at random, some because I like them, some because I think they make good examples. In all cases my goal isn’t to point to these stories for any particular reason, but rather to look at a broad enough range that you can understand how to examine other stories I’ve not included here. Hopefully you’ll find enough use in this to want to do your own studies.

So anyway, let’s get rolling!

Lord of the Rings

Lord of the Rings is a trilogy of novels I probably don’t have to describe here, but I’ll touch loosely anyway. Our protagonist, Frodo, finds out his uncle has been keeping an ancient ring of power, and that said ring attracts the forces of darkness to it. The only way to be rid of it is to throw it into the volcano where it was made.

How does he get this quest? Gandalf, a wizard friend of the family, shows up one day for Uncle Bilbo’s birthday. While visiting, Gandalf finds out about the ring and has a suspicion about it, which he goes off to investigate. He then returns to give Frodo a first quest: bring the ring to the elves. After this, Frodo leaves with his friend Sam to bring the ring to the elves, far away. However, that’s not the main quest. The main quest is the volcano-throwing version, and that comes once Frodo arrives at the elf village. This quest no one gives to Frodo at all. Instead, there’s a big discussion over who should get the quest, and Frodo offers himself once he understands the need. If this were a game, Frodo would have been given the quest in standard fashion by Gandalf, but then once he completed that quest and got its reward, he would simply continue on without being prompted for a new quest.

Ok, so once Frodo is on this quest, what makes it interesting? Well the Nazgul, primarily. So long as Frodo holds the ring, undead wraiths called the Nazgul are drawn to him. He can’t possibly defeat them, so he must avoid their gaze. They only know his specific location if he wears the ring, so the forces of evil send out armies to cover the world, and Frodo must use the ring’s invisibility to avoid them, which draws the Nazgul. There’s also the ring itself which exerts its will on Frodo’s mind, making him want to wear it. The tension of both the desire and need to wear the ring, set against the danger of wearing the ring, is what drives most of the story. Throughout all of this with the Nazgul, Frodo also cannot simply walk into Mordor. He must find dangerous side paths hidden from sight of the evil armies, but filled to the brim with other horrors. Every path Frodo can choose is dangerous in one way or another, and it’s up to him and his companions to choose the danger they think they have the best chance against.

Once the quest is over, the reward is quite simply a return to normalcy. Frodo earns the respect of the people of the world, but his primary reward is to go home and relax for a while. And after such a journey, there’s nothing more that Frodo wants. The more tangible rewards are just icing on the cake, and not given all that much emphasis in the story.

Star Wars

Star Wars is a trilogy of movies in a similar sort of vein to Lord of the Rings. Protagonist Luke Skywalker is a nobody being raised on a farm on a backwoods planet, when suddenly two robots come into his life with a quest that someone must complete for the safety of millions. Luke is in the wrong place at the wrong time and gets swept away on this quest along with a mentor who teaches him about the galaxy. Luke must learn to master his hidden past in order to overthrow the evil dictator who has gained control, before that dictator can blow up planets full of resistance fighters.

How does Luke end up on this quest? Well, a pair of robots stumble into his life without warning. One of those robots has a message that needs to be delivered to someone Luke thinks he knows, so Luke offers to help in this small way. Unfortunately, once he’s done so Luke returns to find his old life has been destroyed while he wasn’t looking, and the person he delivered the message to tells Luke that the only choice now is to leave the planet and go on this quest, which Luke accepts. In this case, there is an explicit quest-giver in this story, two in fact. R2-D2 gives Luke the initial quest, and then Obi Wan gives him the follow-up quest that carries through the rest of the story. Obviously there’s a number of other quests along the way, but those two first quests set the snowball rolling down the hill, and the rest happens as a consequence of momentum.

What makes the quest interesting once Luke is actively pursuing it? Well there’s quite a lot of discovery here, Luke doesn’t know anything at all about the Jedi until he’s told he is one. There’s a lot of hidden information about Luke’s past that he wasn’t aware of, and basically it turns out that Luke has all these connections to this story already and if he’s going to learn the truth about himself, he has to pursue the rest of this. While he’s pursuing this knowledge, the empire is pursuing him. The enemy army is out to destroy the resistance, and the information R2-D2 is carrying, as well as anyone helping. The setup here is similar to LotR in that an evil is pursuing the hero, but the difference is that Vader has many other things to do and only confronts Luke directly when their paths happen to cross. The rest of his time is spent planning the destruction of the resistance. If this were a game, Vader might be a wandering enemy that will gain aggro on the player as long as they’re within the same zone (or some large but arbitrary distance), but wouldn’t seek the player on his own.

The reward of Star Wars is pretty much just survival. Of course there’s a degree of notoriety as well, as Luke earns a few medals in his time, and gains a number of different powers over the course of the movies. But much like Lord of the Rings, Star Wars’ reward is just a return to normal life as best as is possible given the situation. The tangible rewards are mostly inconsequential.

Avatar The Last Airbender

Avatar: The Last Airbender is a tv series that follows 12 year old Aang as he tries to develop his skills and maturity to a point where he can defeat the leader of an enemy army. The story setup is that in every generation there is an Avatar who can use all 4 elements at once (while everyone else only gets a single element), and when Aang finds out he is that avatar, the pressure gets to him and he runs away, ending up trapped in an iceberg for 100 years. Upon waking, he finds out that his absence allowed the Fire Nation to take over the world, and he is the only one who can stop their reign of terror.

The quest here is given to Aang in a vision of a past life of his, where he is told by a spirit that Sozen’s Comet is coming once again, and will give the Fire Nation a temporary boost of power that will make them unstoppable. It’s up to Aang to complete this quest or else every nation will be overrun, and the world knocked out of balance. If this were a videogame, the quest would be a pretty explicit quest giver scenario preceded by a cutscene. This is one of the rare situations where I think the natural instinct of your average game designer is actually the correct choice for this story!

So what makes the quest interesting once Aang’s accepted it? Well he’s far too weak to reach the Fire Nation, much less kill their leader. He’s also morally unwilling to do said killing. Over the course of the show he has to come to terms with his role in society and all the implications of that role. Most of the episodes focus not on the training, but rather on the needs of the people and how the Avatar can and can’t help them. Most of the story is about expectations vs reality. Each episode is an exploration of the perceptions of different people, there are running themes of coming to see the world from others’ perspectives, and the dangers of getting mired in what you think is the right way of doing things. There are also armies and constant battles that happen within this, but the primary driver of the drama is the willingness, unwillingness, ability, or inability to see the world from each others’ view. Most of the fights are directly caused by these perceptions, and the resolution to them is almost never to fight, but only to subdue and teach. Even the final conflict is only combat until the enemy can be subdued and prevented from further violence.

The reward here is once again a return to normalcy. Aang wakes up in a world he inadvertently ruined, and quests until he can bring it back to the way it was.

But enough with this epic nonsense, these are too easy! Let’s look at quest design in things that don’t even have straight forward quests!

Knives Out

Knives Out is a whodunnit story following two characters equally. The perspective character of the film is Marta, a private nurse of the patron of an extremely wealthy family. Though she’s the perspective character we follow through the film, she’s not the protagonist, necessarily. That role belongs to Detective Blanc, who drives the plot forward through most of the film (trading off with Marta a few times). The plot of the film is that the patron has died, and Detective Blanc has been hired to find who’s responsible, but he must do so while Marta tries to hide her involvement. It’s not really possible to objectively say that one of these characters is more important to the story than the other, so I won’t even try. That’s part of why I wanted to examine this movie anyway.

So how do they get their quest? Well Marta wants to prevent anyone from finding out her involvement in the death of her patron, because she knows it would look like she killed him. She got her quest as a consequence of actions the night of the death of her patron, and she didn’t so much accept the quest as she was forced to carry it through to completion or else wind up in jail. Detective Blanc doesn’t even know what the quest is or why he’s been given it. He gets hired to solve a mystery, but only in the form of an envelope full of money and a newspaper clipping. He accepts the “quest” just because he’s so curious what is going on here.

What’s interesting once they’re already on the quest? Well the interest here comes in that Marta’s quest is to prevent Detective Blanc from completing his quest. Not in a direct way, this isn’t some deathmatch fight, that would be too simple. Her goal in this quest is to make Blanc believe he’s completed his quest, but to do so without exposing her role in the mystery. She spends the film foiling his attempts to solve the mystery in laughably ridiculous ways, as the universe seems to conspire to expose her. If this were a game it would be very similar to a game of mafia/werewolf (or Among Us, since that’s the new hotness right now), but with a much more intricate series of ways to expose each other’s guilt (imagine if the scene with the dog happened with a tiny alien walking up to the guilty astronaut in Among Us).

And the reward? Nothing. Nothing at all. There is no reward for this quest, Blanc was hired with cash up-front and Marta earns money over the course of the story, but not as a result of her quest (though there is a time where her money is tied to her completion of her quest, so maybe we could count that).

Beauty And The Beast

Beauty and the Beast is a Disney musical based on a fairy tale. A witch tries to seek shelter with a vain young man who refuses her entry due to her ugliness. She responds by cursing him to be a monster until he can find someone willing to love him. The story follows Belle as she is captured by the beast and eventually falls for him.

So how does she get the quest? Well… she doesn’t. The quest was given to Beast. Technically she does go on a quest of her own volition in the form of rescuing her dad, who she then trades for herself as captor, but that’s not really the main quest, and in this article thus far, we’ve been following just the primary quest of a story. So the beast got the quest, and he was given it in standard quest-giver fashion by someone who set him up with a situation to respond to, and he responded against that person’s preferences. Standard fairy-trickery sort of setup, except that it was ~5 years ago. So the movie actually follows someone other than the child of prophecy, as it were, as they help the failed hero to finally succeed before the time’s up. Belle never chooses to participate in this quest in the quest-giver fashion, she stumbles into the castle and gets trapped by its rules. Once there she promises not to leave, but it’s really up to her to stay. She leaves in the film, more than once, and chooses to come back. Something we don’t often allow players to do in this type of quest.

What makes the quest interesting once we’ve accepted it? Well it’s all intrapersonal relationship stuff as Beast and Belle slowly fall for each other. The quest is really just an excuse for these two to have to spend time together, which maybe isn’t something we map directly into a video game’s systems so much as just something we allow to exist. A quest with no purpose other than to get to know your teammates. What a concept!

The reward here is also in reverse. Belle’s actions complete Beast’s quest, and his reward is a return to normalcy, much like all the rest of these stories I’ve been looking at. Except, again, she isn’t the one getting that quest reward. She reaps the benefits, because she now loves the man, and a man he is once more, but still there’s no direct reward for our protagonist. If this were a game, maybe the player gets a new ally, but no direct reward themself.

Tale of Princess Kaguya

Princess Kaguya follows the story of a young girl who is born into a bamboo reed that’s grown in a forest owned by a simple farmer couple. They raise the bamboo girl as their own, and as they do, a series of miracles happen that provide them with the means to take care of the girl as her family (gods who live on the moon), wish for her.

So how do they get the quest? …..well there isn’t a quest…. A tale, in film speak, is a story told simply as a series of events that don’t follow your typical plot arcs. While Star Wars follows the Hero’s Journey very explicitly, Princess Kaguya needs no such structure. It’s merely a series of events in the life of a young woman whose story then resolves, and we’re left to consider why or if it meant anything at all. The parents get a bunch of money and sort of invent a quest for themselves, but it’s never something they need to follow and indeed they quit before ever completing it anyway. It could be said that Kaguya has a quest in her desire to come to earth for a visit, but if this were a video game the quest on your HUD would read “Go to earth” and would complete the moment the game started.

What makes the quest interesting once they’re on it? Well I suppose the aforementioned miracles are interesting. They just keep getting random gifts from bamboo shoots in the forest, so that’s pretty exciting!

The reward here is a return to normalcy. This series of events happens in the lives of these people, and at the end their lives go back to the way they were, insofar as that’s possible after years of growth and personal development around each other.

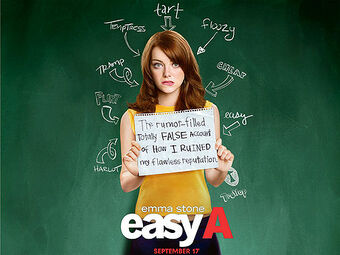

Easy A

Easy A is a romantic comedy film built on tropes from the 80s and intending to lampoon them while delivering a by-the-numbers film in its own right. In it, protagonist Olive must come to terms with her own self-confidence issues as they spiral out of control when she lies to a friend to get out of a boring weekend and keeps up the lie for the sake of appearing interesting.

So how does she get the quest? Well, she tells a lie and the plot sort of happens around her. The “quest” of the film is mostly at the end once she decides how to resolve the conflict of the film by hosting a live webcam show where she tells the story of what’s been happening, though there is a second quest in her need to realize her personal faults. Both of these come to her in the same way: she feels a certain way and acts on that feeling, her motivations are entirely internal. At the start of the film, her internal motivation is that she doesn’t want to hang out with her friend, and she wants to be exciting and popular in high school. At the end of the film, she wants to be rid of the notoriety and the only way out is by telling the truth. She simply decides to do both of those things, and the consequences of her actions play out naturally (if dramatically). If this were a game, there would be no quest giver, she would make a choice that leads to strong reactions from the people around her, and then she would decide that she wants to fix this situation. Another character might decide to roll with it permanently, or to immediately tell the truth and avoid the drama.

Once she’s on the quest, what makes it interesting? Well the main interest in the film comes from the varied reactions people have once Olive tells her lie. Once she’s earned a particular reputation, people treat her very differently. For a time she decides to run with it because this is a reputation she enjoys, but once it all comes crashing down around her she decides to go back to the way things were. All the conflict in this story comes from interpersonal drama. If this were a game, we’d have to represent this by characters having altered dialogue based on a choice the player could make. As long as the player continues making that choice, the conflict escalates and changing their decision becomes increasingly difficult. The climax comes when the consequences start to interfere with the player’s core goal in some way.

The reward for the quest is another return to normalcy. Once again becoming a normal teenager is plenty enough of a reward for this film, though of course there’s also the boy she picks up along the way because this is a rom com afterall.

So that’s all the films I wanted to take a look at today. What did we learn from this examination?

Well, primarily I’ve learned that films and novels find people standing around handing out quests rather boring. Mysterious messages arriving through clandestine means are much more common. Sometimes you find someone who happens to need some help, but even if that’s how the quest starts it NEVER stays that way for long. Kill 10 rats is only ever the beginning of a series of events that snowball out of control wildly.

What’s most interesting to me is the number of times that the quest derives from player choice. Easy A is entirely based on modeling out the NPC reactions to a seemingly inconsequential choice. Imagine if you were to allow a player to put on a mask, but that mask depicts an evil god. Maybe the player thinks the mask looks cool, or that the idea of flaunting the game’s religion is kind of subversive and fun. Once the player starts wearing the mask, the NPCs start to react to that mask. Over time, if the player keeps wearing it, the NPC reactions increase in intensity. Eventually wearing that mask starts to interfere with their other quests and gameplay. Now the player has to make a choice to take the thing off or double down on their mask wearing. This is how quite a few plots work in film, theatre, or novels, but we don’t often model this in games. Obviously it’s because doing so costs a lot of resources for something that may not be all that important, but I can imagine a smaller scale version of this could be implemented at the same level of effort as a normal quest in an open world game.

Another point of interest, for me, are the spaces where there aren’t quests at all. Princess Kaguya is a whole story that just unfolds. This is basically what an emergent narrative looks like, if it had been recorded and set to film. These are just the choices a player makes in response to a game’s systems. Similarly, Beauty and the Beast is all reactive to someone else’s choices. An NPC that has a quest they can’t complete anymore, and is lost to despair. The player can swoop in and help to motivate them, but doing so comes at personal cost. And there’s no reward beyond helping that character complete a quest for themself. We see this sort of thing for helper NPCs in games like Dragon Age: Inquisition, of course, but rarely do we bother doing it for side characters that aren’t direct teammates. I think this would be a really fun way to recruit a character, and we did see this sort of thing for rarer characters in older CRPGs.

And the number one takeaway from all this, for me, is the lack of a quest giver. Quests in other media don’t come from people standing around in an open world, waiting to ask for help. Instead, they exist all around us as we go about our day. If we’re doing quest givers, they should be NPCs yelling for help in the streets as you pass by, ideally with animations to reach out to you as you come close. But beyond that we should get quests as a consequence of our other actions. Game Devs often don’t trust their core mechanics to hold interest (often because their core mechanics just aren’t that interesting on their own). I imagine the ideal scenario for open world quest design is that you walk into a new region and you see a city in the distance. When you get to the city, you find lots of jobs posted on job boards available to you at any time. Let’s say you see a posting to help clear some rats off Farmer MacReedy’s corn field. Kill 10 dire rats, no problem! So you head off to do that, but when you kill the third rat, it drops a magic ring. What on earth is a rat doing holding a magic ring, you ask? So you pick it up and put it into your inventory when suddenly you’re surrounded by ghosts! You can’t even see the corn field anymore for the ghosts, so you throw the ring to the ground and are cured. This destroys the ring, since it’s an MMO or other open world game, but you wonder still. When the seventh rat then drops a similar ring, you stare at it for a moment before picking it up. This time you accept the call, fighting through the ghost blindness to reach the town and ask the local church for help. This starts you down a path that leads you on an epic adventure to kill a necromancer and save both the farm, and the whole city!

And I acknowledge that players aren’t going to enjoy being blinded, and a number of other concessions that should be acknowledged in my example, I’ve not put it into full production, but surely you can imagine a few tweaks to the standard formula that could give us a ton of variety at very little cost. Quests that begin on picking up an item don’t really need more resources to create, since you already have quests, items, and an inventory. Ghost blindness may not work for you, but maybe you start shooting fire from your face or something. Your game definitely has systems that can be used here, even if you’re a turn-based game no more complex than the original Final Fantasy.

Imagine a world where you’re a wizard learning your level 15 skills and you find a book of dark magics somewhere. You see this really amazing spell in there, so you learn it, but once you do you become marked by the Wizard Council who demands you burn that book and never use that spell again. Technically this isn’t more complex than any Dragon Age quest, but it’s going to stick with you a lot longer because it came directly from a choice you made, and one you weren’t making in the context of a quest.

All player choices can create consequences. Some of those consequences can be “quests”, either immediately or revealed over the course of time. There’s quite a lot of research on player expression, autonomy, etc. and there’s a whole field of study into self determination theory, all of which basically says “I like it when things respond to my choices”.

I believe there’s a broad range of untapped potential in games to offer responses to player choice. I also believe that most of that can be done without any additional workload or at any greater cost of resources than we already expend on less engaging options. By looking into the way other media approaches its stories and quests, I believe we can learn to improve our medium and bring games into the future.

To this end, keep an eye on this blog as I’ll be going much harder into this quest design research over the coming months.

And as always, thanks for reading!